In these posts I share my favorite discoveries from my chronological travels through manga history. From timeless classics to hidden gems. It’s been ages… but finally I found the time to continue this series about early manga. 1972 was a strong year and decent one for the female protagonist I’d say. So I’m happy to jump back into it with this impressive selection of works. Fans of early “gender bending” shoujo and Quentin Tarantino might find something to their liking here. Again, for context, I’m adding some manga titles already publishing during this time. So here’s the best manga of 1972!

The best manga of 1972

POPULAR MANGA PUBLISHING IN 1972:

- Cyborg 009 (1964-1979)

- Sabu to Ichi Torimonohikae (1966-1972)

- Ashita no Joe (1968-1973)

- Doraemon (1969-1996)

- Lone Wolf and Cub (1970-1976)

- Sasori (1970-1975)

- Sangokushi (1971-1986)

BEST MANGA DEBUTING IN 1972:

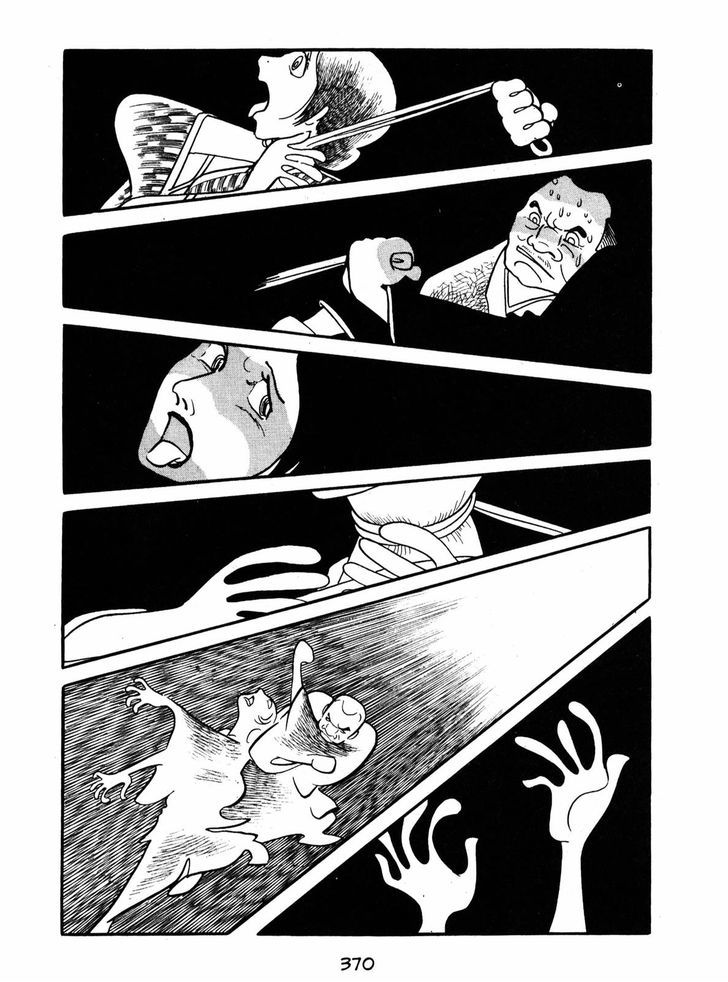

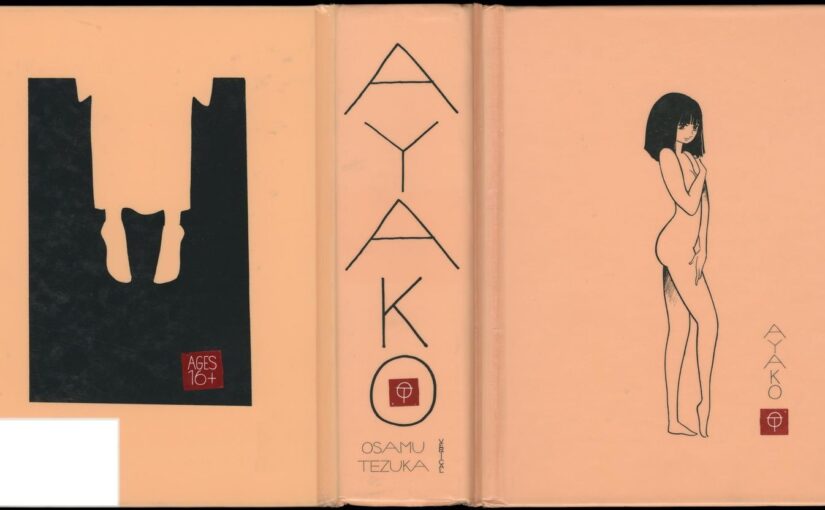

AYAKO – OSAMU TEZUKA, Jan 1972 – Jun 1973

Ayako is one of Osamu Tezuka’s most famous works, one of the few manga most consistently found in the shelves in your local bookstore even if they barely have manga to sell at all. Tezuka’s creative output has been impressive for years, but he’s seriously peeking here. Ayako is a dark criticism of Japan and its fate in the aftermath of World War II, with Ayako herself as the symbol of things left unseen following the war.

It features some of Tezuka’s strongest moments, both in artwork as in storytelling. Every character is heavily flawed and even the male lead at time performs unforgivable actions. Which is something I struggle with in his work at this point in time. Nonetheless it is a testament to what manga (and Tezuka himself) can do.

BUDDHA – OSAMU TEZUKA, Sep 1972-Nov 1983

Buddha is Tezuka’s both gritty and comical interpretation of the life of the founder of Buddhism. 20 million copies in circulation, Eisner award winning, used in Buddhist temples for young adults to learn about the life of Buddha… I’ll spare the praise for now, just know that this is a large epic, and only not considered to be his magnum opus because Phoenix exists. Honestly, if you’re on this blog and you haven’t heard of Tezuka’s Buddha, I don’t know what to tell you.

LADY SNOWBLOOD – KAZUO KOIKE, KAZUO KAMIMURA, Feb 1972 – Feb 1973

Lady Snowblood is basically the OG Kill Bill. And I mean that quite literally as the manga (or maybe more so the 1973 movie based on the manga) was a major source of inspiration for Quentin Tarantino. Lady Snowblood is a revenge story with a simple plot, but every chapter is a thrill to read with pages begging for a big screen adaptation. Which it did, in December 1973. The Japanese don’t waste any time.

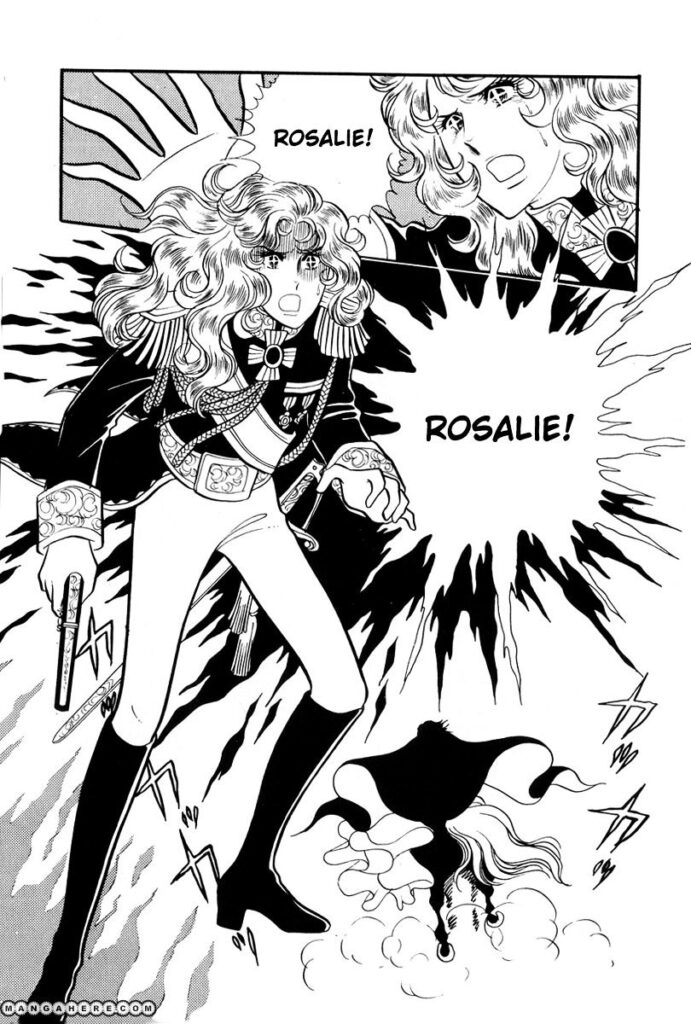

THE ROSE OF VERSAILLES – RIYOKO IKEDA, 1972-1973

Versailles no Bara or The Rose of Versailles focuses on the lives of two women: Marie Antoinette, the Queen of France and Oscar François de Jarjayes, who serves as commander of the Royal Guard.

At this time, shoujo manga was going through a significant transitional period, characterized by stories with complex narratives, focusing on politics and sexuality. Riyoko Ikeda in particular became involved in the Japan Communist Party, during the rise of the New Left in Japan. The publishing of a story set during the French Revolution was no accident. Several of her early works are socially and politically motivated and address themes like poverty or discrimination. Ikeda is also associated with the so-called “Year 24 Group”, a group of female mangaka born in or around year 24 of the Showa era (1949).

Rose of Versailles was intended to be a biography of Marie Antoinette, following Ikeda’s decision to create a manga focused on themes of revolution and populist uprising. Her editors did not support this concept, so she relied on feedback from fans to determine the direction of the story. Oscar was initially introduced as a supporting character. But this strong, charismatic androgynous character resonated with the shoujo audience and ended up eclipsing Antoinette to become the main character.

Readers with feminist convictions might be very interested in reading further analyses about the complex characters and romantic relationships within the stories and how they echo typical or non-typical heroines and situations from the shoujo or the emerging boy-love genre. Other readers can just revel in the compelling storyline and the beautiful rococo art style.

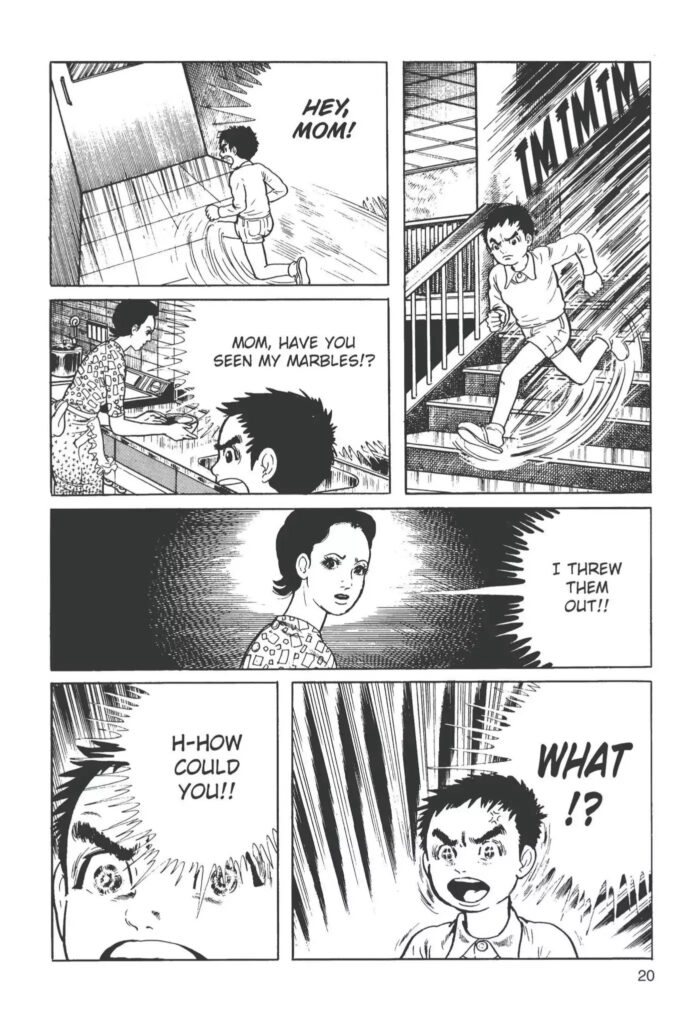

THE DRIFTING CLASSROOM – KAZUO UMEZU, 1972-1974

Award winning and somewhat of a classic in the horror manga genre, followed by several adaptations. From the grandmaster himself, Kazuo Umezu. Hyouryuu Kyoushitsu or The Drifting Classroom is like a Lord of the Flies in a post-apocalyptic nightmare setting. It shows its age in the art, the poorly explained sci-fi elements and dumb choices the characters make for conflict’s sake. It’s suspenseful nonetheless, with one gruesome situation after the other and has many questions raised but rarely answered. The Drifting Classroom is an utterly frustrating read, but equally hard to put down. A must-read for fans of the genre or those interested in the evolution of early manga.

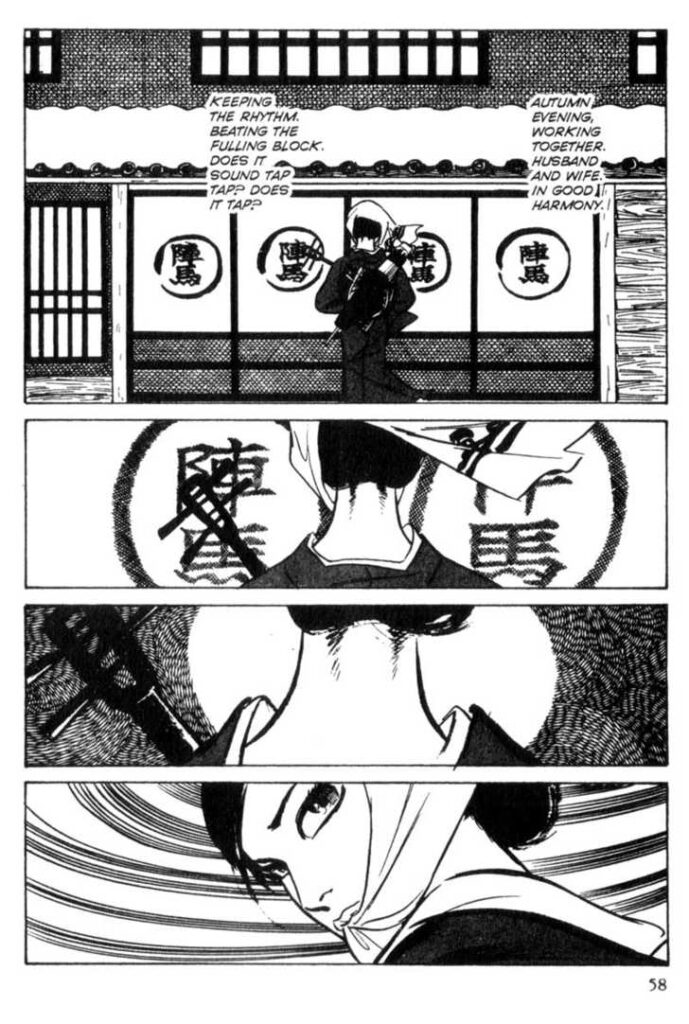

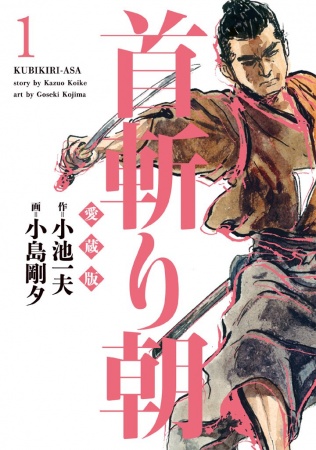

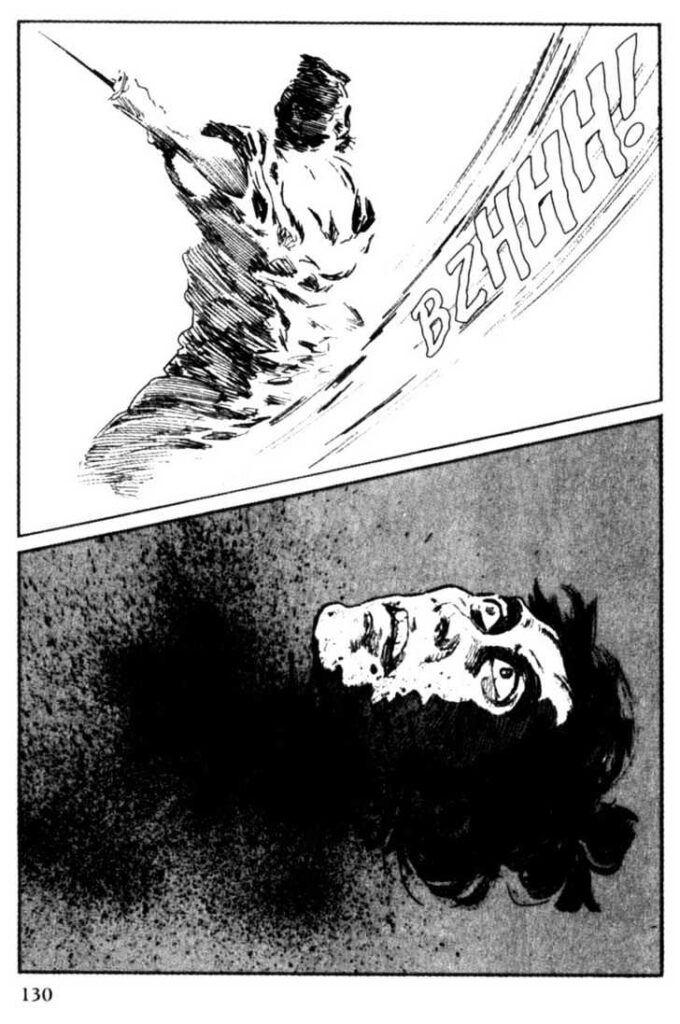

SAMURAI EXECUTIONER – KAZUO KOIKE & GOSEKI KOJIMA, 1972-1976

Kubikiri Asa or Samurai Executioner is another result of the highly successful partnership between Kojima and Koike. Serialized during the publication of Lone Wolf and Cubit seems these two still had some time on their hands.

It’s near impossible for Samurai Executioner to not find itself in the shadow of the timeless classic that is Lone Wolf and Cub. But it deserves a look nonetheless, if not just for the gorgeous art style. Samurai Executioner revolves around Yamada Asaemon, a samurai responsible for testing swords for the shogun and called upon to perform executions. Often focusing on the stories of the criminals he executes, the manga somewhat lacks an overarching narrative, but I’m a bit of a sucker for standalone vignettes too. Each chapter has an thought-provoking tale based on the moral dilemma’s that bushido and justice present.

Let’s get one thing out of the way though. Bushido, basically the samurai moral code, is silly. Koike and Gojima are conservative writers. The male characters excel at machismo and all the female characters excel at is being victimized. There’s no way around this. And maybe for this style, basically the Japanese equivalent of a spaghetti western, that’s completely fine. But you will see the “heroes” do things you might have moral objections to. Take it as it is, and I hope you will enjoy it as much as I do. Kubikiri Asa receives some criticism online, but it’s one of my personal favorites. Savor over time.

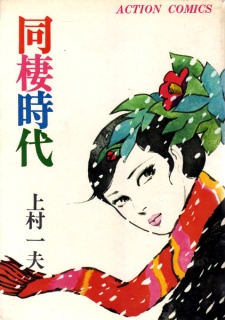

DOUSEI JIDAI – KAZUO KAMIMURA, feb 72-oct 73

Dousei Jidai is a recent discovery. Not even halfway through I can safely say that this is an absolute masterpiece. An instant best seller when it came out right around the end of a protesting movement in Japan, it apparently resonated strongly with students during this time, uncertain and anxious about their futures.

Essentially a love story, but the love here is passionate, raw, violent and impulsive. Jiro and Kyoko are an unmarried couple living together. Jiro is a struggling illustrator, Kyoko has a steady job, but is undervalued because of her gender. Some chapters show glimpses of happy, contemplative and beautiful moments in their relationship, cherishing the present. In others they are violent with each other, cheat or openly discuss the possibility of a love suicide.

The tragic nature of this relationship is clear to the reader from the beginning. How it will end, one can easily imagine. Unfortunately scanlation is still slowly ongoing, yours truly is currently waiting at 24 out of 80 chapters and dying. Hidden gem searchers, look no further, but prepare to be frustrated.

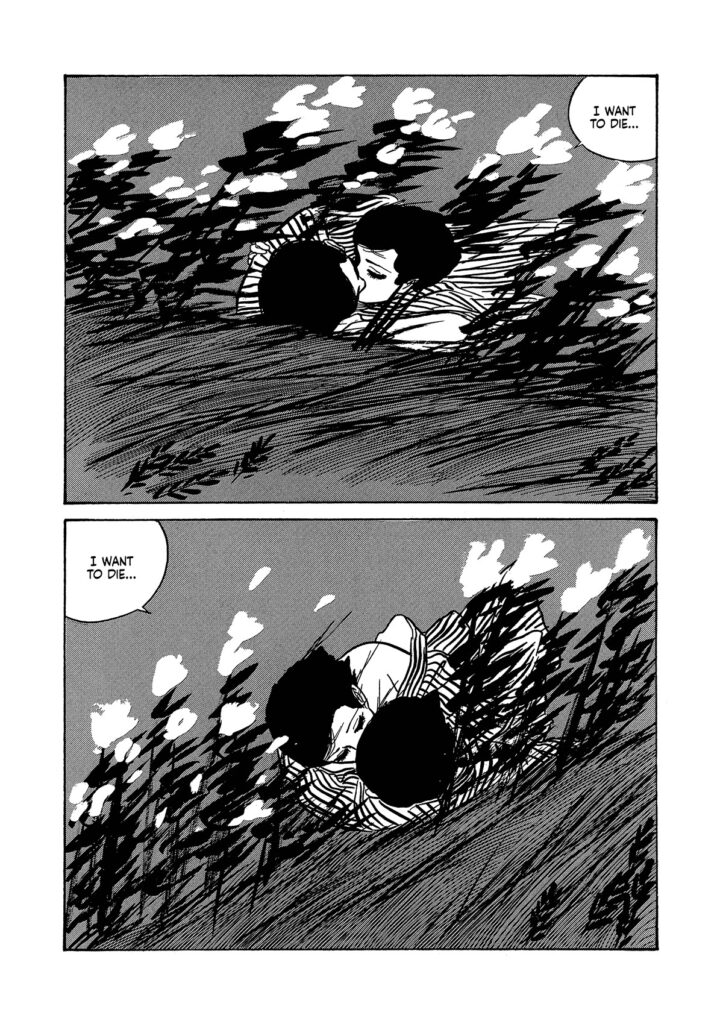

MAYA NO SOURETSU – YUKARI ICHIJO, 1972

Another good example of 70’s shoujo manga. Maya’s Funeral Procession is a somewhat more “typical” girl-love story than Rose of Versailles. By that I mean a “heterosexual” girl falling for another girl. There’s big twists though and more than just romance, and perhaps enjoyable to people who aren’t fan of the genre. Maya’s Funeral Procession stood out for me because of the artwork. While aged and at certain moments quite resemblant of Tezuka, there’s a maturity compared to others within the timeframe. The plottwists and pushing of social norms didn’t hurt either. Only 4 chapters long, so why not give it a try.

Honorable Mentions

MAZINGER Z – GO NAGAI, Oct 1972- Aug 1973

One of the first Super Robot manga and definitely one that introduced many of the traits of the Mecha genre. Neither Go Nagai or old robot manga are my cup of tea, but definitely worth a mention at least.

HENSHIN NINJA ARASHI – SHOUTAROU ISHINOMORI, 1972

This is one of those times where I regret not making notes at the time of reading, because I hardly remember this, but I have a soft spot for Shoutarou Ishinomori. Some might pin him down as a Tezuka clone, but I think he’s just a bit more elegant in his artwork and there’s more “feeling” to his stories and characters. This manga is filled with action and gory scenes and I remember having fun with it, but that’s as far as my recollection goes.

ROBOT KEIJI – SHOUTAROU ISHINOMORI, Dec 1972-Sep 1973

Manga version of the live action series. Very good read, but with so many great manga for this year, it’s banned to this category as well.

HANSHIN – HAGIO MOTO, 1972

Not sure if I’m correct with the date here, but I’m a fan of Hagio Moto’s work and I wanted to mention this slightly disturbing one-shot.

That concludes my picks for best manga of 1972. Do I have awful taste? Think I didn’t make enough effort? Share it in the comments or write your own damn blog. Or did I unforgivably overlook your favourite manga? In that case I might actually be interested. Please share your thoughts!

Next post:

Best manga of 1973

Previous post:

The best manga of 1971

✨